You can’t book them and you don’t know who else will be there, but they’re an excellent way to explore Britain’s most remote corners – for free.

Hiking up to the top of a valley in Wales’ Cambrian Mountains, I was struck by the silence. The noise of the modern world that we’ve trained ourselves to filter out becomes conspicuous by its absence. This is probably the best indication that you’ve entered one of Britain’s remote places, and a good sign if you’re trying to find a bothy, one of the free-to-use shelters that dot the country’s wild areas.

Founded in 1965, the Mountain Bothy Association (MBA) is a registered charity that maintains “simple shelters in remote country for the use of all who love wild and lonely places”. The organisation manages more than 100 bothies in Scotland, Wales and Northern England.

The system is simple. Bothies are free to use and open to anyone. They can’t be booked in advance, and there’s an unwritten rule that the bothy is never full (although groups of six or more and commercial groups are asked not to use them). As long as you follow the MBA’s Bothy Code, which is based on respect for other users, the bothy and the surroundings, you’re welcome.

That is if you can find them. Although the grid references are available online, don’t count on phone signal when looking for them, and even with a well-marked map, they can prove elusive.

I was hiking a network of trails in an area known as the “Green Desert of Wales” because of its lack of settlements, roads and infrastructure. I planned to sleep at Nant Syddion bothy before heading to Aberystwyth, the largest nearby town, the next day. Given the relative scarcity of buildings in the landscape, I’d expected to locate the bothy easily. But climbing up and down a succession of forestry tracks as the sun began to set, I began to wonder if I was going to find it at all.

With relief, I finally caught the reflection of a window through the trees and climbed down a steep path to a two-storey stone building that looked like a home transported into the middle of nowhere, complete with a spiral of smoke climbing out of the chimney. And that’s exactly what it was. Nant Syddion used to be home to a lead miner and his family and now provides a temporary home for hikers.

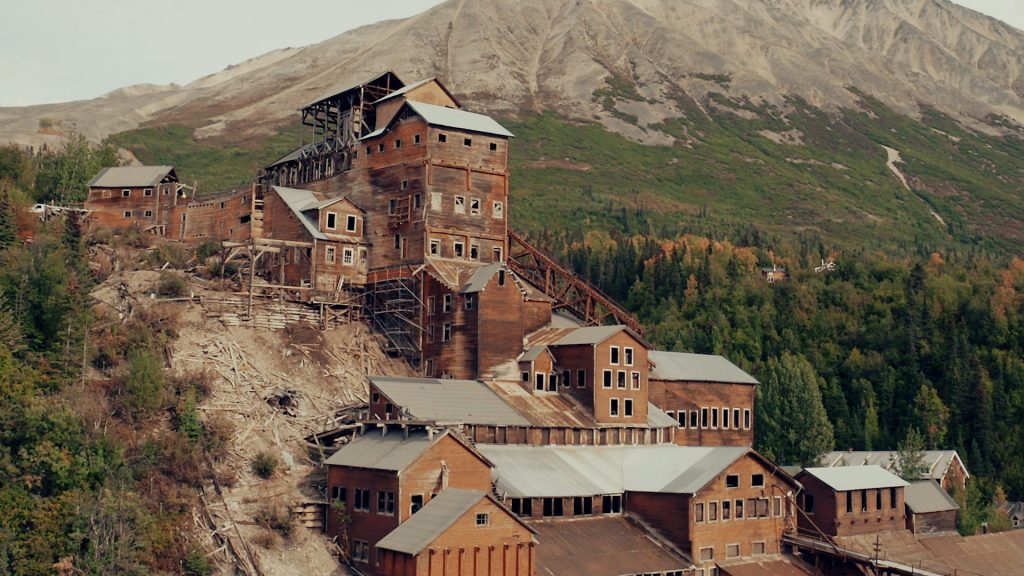

Every bothy is an adapted building with a previous life. Most are old shepherd’s huts, farmsteads or workers’ accommodation. In the early 20th Century, hill farming declined and fewer and fewer people lived in remote locations, leaving many buildings derelict. After World War Two, hiking and mountaineering as leisure pursuits dramatically increased in popularity and those exploring the outdoors began using these abandoned buildings as shelters. The MBA was created by Bernard Heath and a group of friends to restore and maintain them for like-minded individuals.

Remote upland country takes its toll on buildings; the wind and rain age, erode and wear almost everything. However, arriving at the bothy, I found that everything was watertight and functional. Even the gate and the front door had recently been painted.

Keeping 100 buildings habitable in some of the remotest parts of Britain is no mean feat. When you factor in that this work is all done by volunteers (and where bothies have toilets, it involves carrying the waste out), it’s a step beyond altruism. Each bothy has two maintenance organisers, and work parties are organised for any large-scale or structural jobs, which, Neil Stewart, head of communications at the MBA, told me, are rarely lacking in willing hands.

Although they’re maintained, bothies are by no means luxurious. You won’t find electricity or running water and will be lucky to have a long-drop toilet. Most will have a stove, but there’s no guarantee a supply of fuel will be there. Your comforts are carried in, and you should pack as if you’re camping, including a tent if the bothy is overcrowded or you don’t fancy the company.

The company you find in bothies, and the fact that it’s completely unpredictable, is one of their unique attractions, according to Phoebe Smith, author The Book of the Bothy. “In a world where everything is bookable and controllable, I love that you can’t do that with a bothy,” she said. “You just have to go and turn up, and you could have it all to yourself or you could meet some incredible people and share some incredible memories. [Bothies] connect you with other people.”

When I arrived at Nant Syddion, there were already two cyclists in the main room who were doing an off-road tour of the area. I laid out my roll mat and sleeping bag in the last unoccupied upstairs room and went to join them.

After introducing myself to the cyclists, Alex and Simon, I prepared a quick meal over my gas stove while they battled to get the fire to take. Built to withstand its exposed position, the bothy had thick walls and small windows, so when the light began to disappear, it got dark quickly. We lit a succession of candles and arranged our chairs in a semicircle around the roaring fire.

One of the best parts of bothying for me is that people are drawn to socialise together – although you’re under no obligation if you want your own space. As we warmed up by the fire, one, then two bottles of whisky (something of a traditional drink for bothies) did the round and stories began to flow. We talked about recent hiking trips in the Dolomites and our bothy experiences, arriving at one to find it full of ex-soldiers in the middle of a reunion drinking session. Hours passed and laughter continued until we remembered we had to hike and cycle back out the next day, and reluctantly left the warmth of the main room to sleep.

A feature of every bothy is the bothy book, where people record their experiences and motivations for visiting. The next morning, I read through accounts ranging from people sheltering from the rain to alleged supernatural happenings. There was an entry roughly every couple of days, indicating a steady flow of people passing through.

However, it’s only been in the last decade and a half that bothies have shifted away from being something of a closed society. In 2009, the locations of the MBA bothies were shared online by the organisation. “It used to be quite a secretive organisation in the sense that people found out where the bothies were by joining the association or just coming across them in the wilderness areas,” Stewart explained. “But that was unsustainable with the internet and people using the outdoors. And it was against our charitable aim. If we’re providing buildings for people to use, it’s logical we have to tell them where they are, we can’t leave them secret.”

This move wasn’t unanimously popular. Part of the concern was that the people might begin using these spaces as places to party as opposed to a shelter while enjoying outdoor pursuits. But, as Stewart told me, it’s not a problem that’s unique to bothies. “We have had examples of drinking parties in bothies, but we’re not particularly bothered with that… There are problems with wild camping in many areas of the country. Up in Scotland, there’s a ban on wild camping in one of the national parks because people were littering, leaving rubbish [and] cutting down trees for fires.”

Cre: BBC