A Baroque masterpiece once believed lost to history has reemerged from the rubble of Beirut’s 2020 explosion. Hercules and Omphale, a 17th-century oil painting by Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi, was severely damaged during the blast but has now been meticulously restored over three years. For the first time in its history, the painting is on public view at the Getty Center in Los Angeles — a resurrection that underscores both the fragility and resilience of great art.

A survivor of tragedy and time

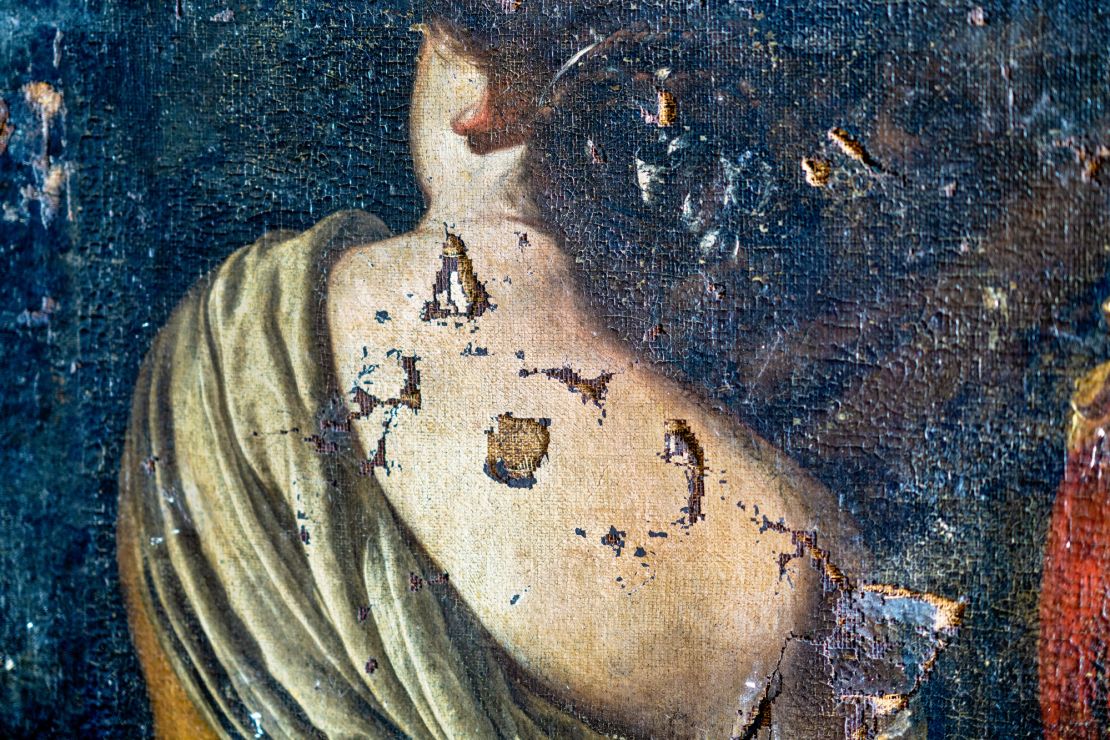

When the massive explosion rocked the Lebanese capital in August 2020, it left a path of destruction that reached into the heart of Beirut’s cultural legacy. One unexpected victim was Hercules and Omphale, a monumental oil-on-canvas painting that had hung for decades in the historic Sursock Palace. Positioned directly in front of a window, the artwork was punctured by shards of glass and covered in debris. Among the blast’s human toll was 98-year-old Yvonne Sursock Cochrane, matriarch of the family who had preserved the palace and its collection for generations.

The painting had remained a private treasure for nearly 400 years, having passed between only three collectors since its creation in the 1630s. It was not just its physical form that had been obscured by time, but its very authorship. Only after the explosion did the painting receive full and formal attribution to Artemisia Gentileschi — one of the most important and trailblazing female painters of the Baroque era.

Now, as part of the Getty Center’s exhibition Artemisia’s Strong Women: Rescuing a Masterpiece, the painting is finally receiving the recognition it was long denied. With luminous skin tones, luxurious textiles, and powerful emotional nuance, Hercules and Omphale captures Gentileschi’s hallmark fusion of drama and intimacy — even as it bears visible scars of its near-destruction.

Reconstructing a forgotten icon

The road to recovery for Hercules and Omphale was far from straightforward. When Getty Museum conservator Ulrich Birkmaier first laid eyes on the torn and dust-covered canvas, he faced what he called “the worst damage I’ve ever seen.” Beyond the L-shaped tear slicing through Hercules’ knee, the surface was riddled with cracks, discolored varnish, and overpainting from earlier, less skilled restorations. The painting had also suffered from the humid Beirut climate, which caused paint to flake and warp.

Restoration involved not just technical mastery but deep historical research. Using X-ray imaging and XRF mapping, conservators were able to detect underlying sketches and compositional changes made by Gentileschi herself. Hercules’ head, for example, had been slightly repositioned in the final version to emphasize the emotional pull between the two figures — a decision that Birkmaier described as “very much Artemisia.”

In a unique collaboration, Birkmaier enlisted the help of Federico Castelluccio — actor and Baroque art collector best known for his role as Furio in The Sopranos. Castelluccio helped recreate Hercules’ damaged facial features based on period techniques and known stylistic elements. But Birkmaier was careful not to aim for perfection: “Restoring an old work doesn’t mean making it like new,” he said. “It means honoring the decay from time while allowing the image to breathe again.”

Rediscovering Artemisia’s genius

While Gentileschi is now celebrated as a feminist icon and artistic innovator, she was long overlooked by mainstream art history. The daughter of the painter Orazio Gentileschi, she trained in his studio and absorbed techniques from Baroque luminaries such as Caravaggio. She traveled across Italy and Europe, taking commissions from the Medici family, the Spanish court, and Charles I of England. Still, her reputation faded after her death in 1653, as was the fate of many female artists of the era.

The painting’s rediscovery was first hinted at in the 1990s, when Lebanese art historian Gregory Buchakjian linked it to Gentileschi while studying the Sursock collection. However, his theory remained unpublished for decades. It wasn’t until 2020 — in the wake of the explosion — that he published his findings in Apollo magazine, prompting widespread scholarly consensus around the painting’s authorship.

The Getty’s exhibition offers more than just a restored masterpiece. It provides rare insight into Gentileschi’s evolving style. Senior curator Davide Gasparotto noted that this period of her life, spent in Naples, has often been dismissed by art historians as less significant. Yet Hercules and Omphale tells a different story — one of growing ambition, scale, and complexity. “Her paintings grow in size. They are monumental, multi-figure compositions,” said Gasparotto. “And Hercules here is perhaps her most accomplished male figure — remarkable for an artist who wasn’t allowed to study the male nude.”

Women, power, and the Baroque lens

In Hercules and Omphale, Gentileschi turns a classical myth into a quiet meditation on gender and power. Hercules — the epitome of masculine strength — is shown not wielding a club, but holding a spindle of wool, performing domestic tasks for his captor-turned-lover Omphale. It’s a scene of intimacy and role reversal, in which Omphale’s gaze and posture reflect quiet authority. This subversion of traditional roles was a recurring theme in Gentileschi’s work, also evident in her best-known painting, Judith Slaying Holofernes.

“She had a poetic touch in how she portrayed women,” said Birkmaier, pointing to Omphale’s subtle head tilt — a signature pose that appears in several of Gentileschi’s female figures, including Susanna and the Elders, recently rediscovered in the UK’s Royal Collection. While Gentileschi’s canon is slowly expanding, many of her works remain lost, misattributed, or obscured by collaboration with workshop assistants. Still, recent high-profile rediscoveries, including a David with the Head of Goliath slated for auction at Sotheby’s, suggest there is more of her legacy waiting to be uncovered.

Art that endures

Hercules and Omphale stands today not only as a restored painting but as a symbol of cultural resilience. From private obscurity to public acclaim, and from near-ruin to revival, its journey mirrors the arc of Gentileschi’s own reputation — long sidelined, now finally in the light.

“You have this painting in pieces… and then little by little, as you work on it, the image emerges again,” Birkmaier reflected. “It’s a really interesting process of discovery. I wanted to do her justice.” Indeed, justice — artistic, historical, and symbolic — has finally been served.