Robert Altman’s 1992 film The Player remains a scathing satire of Hollywood’s corporate machine and creative compromises—one that resonates more sharply today than ever before. As Apple TV+’s The Studio reboots the story of film executives grappling with a shifting industry, Altman’s original vision of Griffin Mill, the cynical studio head embroiled in murder and machinations, provides a timeless lens through which to view the perennial conflicts of art and commerce in moviemaking. While The Studio infuses modern slapstick and workplace comedy, The Player delivers a darker, more bitter critique of the studio system’s enduring flaws and the fading role of true artistry.

Hollywood’s fading artistry: Altman’s biting portrait

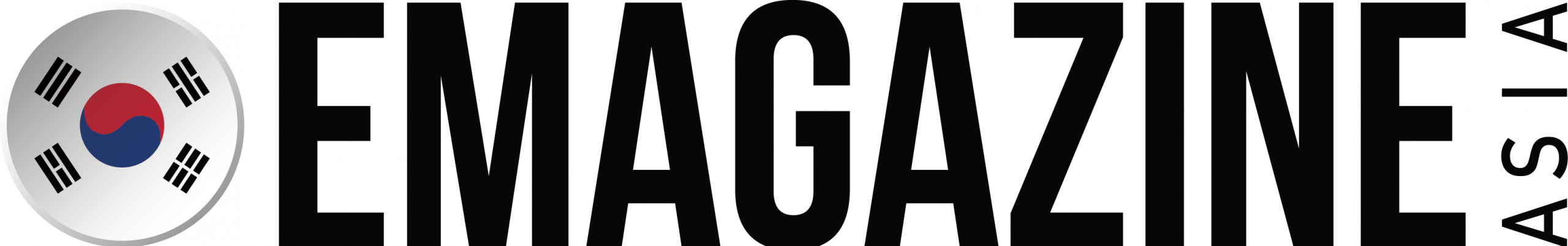

The Player introduces Griffin Mill, portrayed by Tim Robbins, as the archetype of the self-absorbed Hollywood executive. Draped in double-breasted suits and juggling endless celebrity cameos, Mill embodies the cold corporate side of moviemaking. His disinterest in the screenwriters pitching desperate ideas contrasts sharply with his superficial charm and obsession with status. Unlike The Studio, which centers on a studio chief nostalgic for a bygone era of “artists first,” The Player exposes a world where filmmakers only matter when threatened by violence.

Mill’s world is a sterile office park filled with fax machines and trivial distractions—far from the glamor typically associated with Hollywood. The film only gains its cinematic magic when anonymous death threats force Mill into a noir-like spiral of paranoia and crime. This dark narrative, adapted from Michael Tolkin’s novel, elevates the satire beyond mere industry commentary, turning it into a grim meditation on a Hollywood that once balanced art with commerce but now flounders in corporatization and cynicism.

The studio vs. the player: A tale of two eras

While The Studio leans into modern workplace comedy tropes with long tracking shots and frantic energy, The Player remains a masterclass in tone and technique. Altman’s iconic opening eight-minute “oner” not only showcases his virtuoso filmmaking but also satirizes Hollywood’s shift towards quick-cut editing, lamenting the loss of meticulous cinematic craftsmanship. This contrast sets the stage for the film’s broader critique of industry trends.

Unlike The Studio, which rarely references classic films or filmmakers beyond name-drops, The Player is steeped in cinematic history and culture. Characters discuss legacy projects like The Graduate and Bicycle Thieves, underscoring a connection to film as an art form. The film’s centerpiece, the fictional legal drama Habeas Corpus, culminates in a cynical sellout sequence that feels increasingly rare in today’s franchise-driven, streaming-dominated landscape. This reverence for cinema’s past adds layers of poignancy to The Player’s critique of Hollywood’s current creative bankruptcy.

Larry Levy and the death of creativity

One of the film’s most cutting moments comes from Larry Levy, Griffin Mill’s ruthlessly smug rival played by Peter Gallagher. Levy embodies the corporate mindset that sees creative types as obsolete relics, advocating for formulaic, profit-driven filmmaking. His knack for turning random headlines into clichéd script pitches mocks Hollywood’s reliance on templated storytelling and its disdain for original voices.

Gallagher’s portrayal is both charismatic and menacing, highlighting how the industry’s embrace of mass-market tropes threatens genuine artistry. With generative AI and algorithm-driven content creation on the rise today, Levy’s disdain for writers and original ideas feels eerily prophetic. When Mill jokes about eliminating actors and directors, the line crosses from satire into uncomfortable reality, underscoring the growing tension between technology, commerce, and creativity in filmmaking.

A bleak look at the business of movies

The Player delivers a darkly humorous yet sobering vision of Hollywood’s future. Mill’s declaration that a successful film needs “suspense, laughter, violence, hope, heart, nudity, sex, happy endings” echoes the reductive demands studios still face, but today’s focus has shifted to prestige TV and endless franchises. Unlike The Player’s era, where even a bland optimism like “Movies, now more than ever!” felt believable, contemporary Hollywood often seems trapped in a cycle of endless sequels and spin-offs that resist closure or meaning.

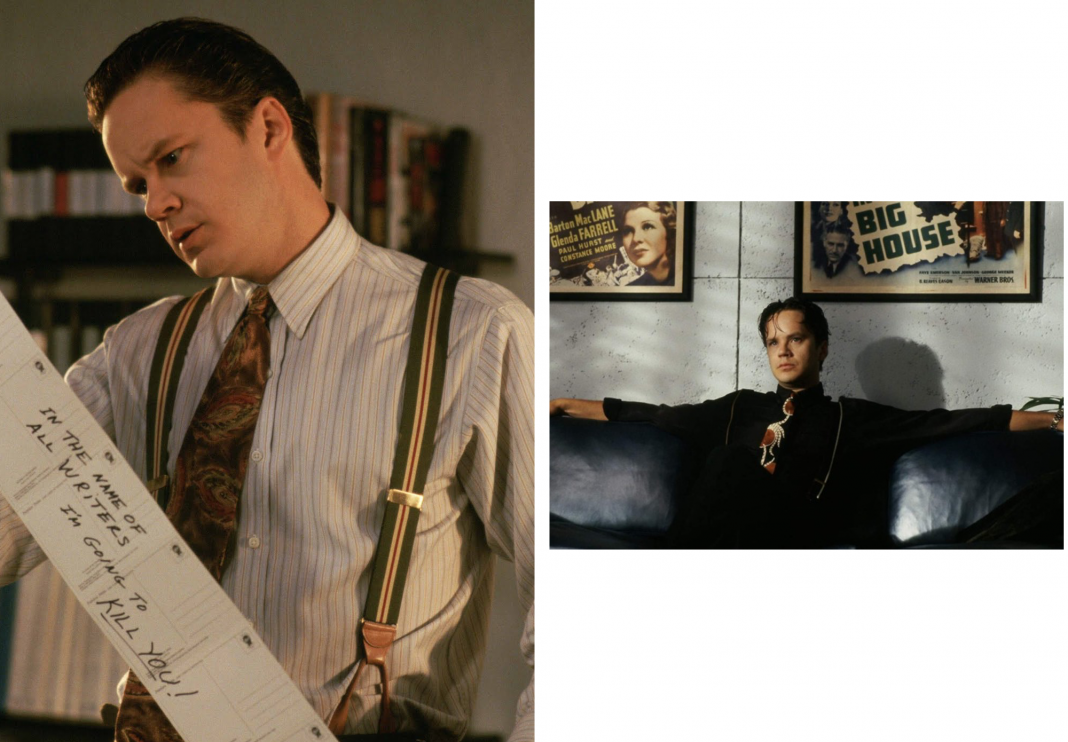

The recent season finale of The Studio captures this exhaustion with its surreal scene of a puppet-like executive chanting “Movies! Movies! Movies!” The bleakness here surpasses Altman’s film: where The Player offered a faint glimmer of hope through its characters’ flawed humanity, The Studio presents a world where even that hope feels performative and worn thin. Altman’s satire, in hindsight, remains a crucial benchmark for understanding how far Hollywood’s industry and its attitudes have evolved—and perhaps devolved—in the decades since.

As The Studio brings a fresh, chaotic energy to the story of Hollywood’s struggles, The Player stands as a timeless, incisive critique of an industry perpetually caught between creativity and commerce. Its biting satire continues to resonate as the film business faces new challenges, making Griffin Mill’s story more relevant than ever. For anyone interested in the darkly comic underbelly of moviemaking, The Player remains an essential, sharp-edged masterpiece.