In every conceivable way, 1999 was a phenomenal year for movies, meaning Magnolia was just one great film in a sea of many. The stars had aligned, or maybe technology permitted filmmakers to realize things to their full potential, or maybe there was something in the water down Hollywood way, or maybe it was all of the above, plus who knows how many other things. That all means it’s hard to call Magnolia the best film of its year, considering its competition included the likes of Toy Story 2, American Beauty, Fight Club, The Matrix, and Eyes Wide Shut, to name a few, but Magnolia can still stand tall among such films and, overall, has aged surprisingly well in the quarter of a century that’s passed since it was first released.

Magnolia has celebrated such an anniversary at the end of 2024, well and truly standing as a classic; one that was generally revered to some extent upon release, but has only become more impressive as time has marched on. In that time, it’s remained novel, bold, and maybe even revolutionary. With a complex structure, a combination of maximalist style and grounded drama, some thematic content that’s aged scarily well, and an overall boldness on the part of a young Paul Thomas Anderson at the height of his powers, Magnolia still soars when watched 25 years on from its first release. It is a long, challenging, bombastic, and sometimes confounding watch, but it’s hard to imagine anyone sitting down to give the film its time and then subsequently coming away from the viewing experience empty-handed.

What Is ‘Magnolia’ About?

It might be a cop-out of sorts to admit, but the basic plot of Magnolia isn’t too important in the end, because it’s all about the smaller stories contained within this behemoth of a film. It runs for more than three hours overall, and finds more than enough interesting characters and issues to explore during that time. It has an ensemble cast and a runtime that might make one think they’re about to watch an epic, but then Magnolia subverts expectations by not telling one particularly grand story, nor worrying all that much about outward spectacle. The numerous characters have lives that sometimes intersect, but their lives are only viewed over a short period of time, with all the events of Magnolia taking place over a single day (admittedly, this excludes the wild, more fractured, and appropriately mood-setting prologue).

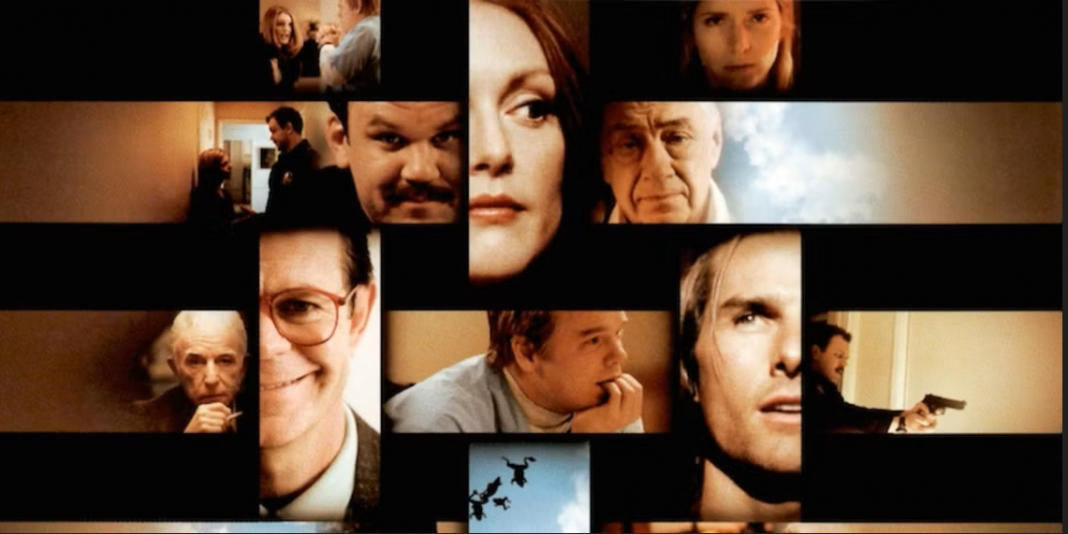

Various characters are explored throughout Magnolia’s complex and admirable screenplay. One man, played by Jason Robards, is dying of cancer, and his story pulls in his hospice nurse (Philip Seymour Hoffman), his struggling younger wife (Julianne Moore), and his estranged son (Tom Cruise), the latter being introduced as a sleazy and domineering self-help guru. Another troubled father (played by Philip Baker Hall) is the host of a game show, and he has a strained relationship with his daughter (Melora Walters), and she has a budding relationship with an LAPD beat cop (John C. Reilly)… but, back to the game show, the current young contestant on it, Jeremy Blackman (Stanley Spector) is going through his own struggles, as is a former contestant (William H. Macy) who feels he peaked early in life, having been a child on the show decades earlier. And that’s just scratching the surface. The conflict each character is caught up in proves engrossing, the way they sometimes cross paths is thrilling, and then the way they’re all impacted by an impossible-to-predict final act plot twist of sorts… well, that last part has to be seen to have any chance of being believed.

What ‘Magnolia’ Represented for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Body of Work

So, for all the talk of that wild ending (which still won’t be spoiled here), Magnolia was, admittedly, willing to break from reality before its final few scenes. In a sequence more brazen than just about anything Paul Thomas Anderson has directed since the start of the 21st century, Magnolia’s disparate characters are temporarily united through a montage; not just by their shared misery at the things in their respective lives, but by a single song: “Wise Up” by Aimee Mann. It’s perhaps the film at its most moving, but also close to its most out-there. Some might call it ridiculous and reality-breaking, while others might recognize it as something tremendously moving and poetic, realism be damned.

Melodrama is a four-syllable word that begins with “M” and ends in “a,” and so is Magnolia. Magnolia is melodrama done right. In a film like this, people can clash with each other in ways that might otherwise feel contrived, but if you get the tone right, it feels like destinies colliding. People can all be united by a tremendously moving ballad, even singing along, making the whole thing feel – for a handful of minutes – like a musical. Then, after three hours, things can get biblical, because why not? Magnolia was a movie that clearly had a filmmaker behind it whose motto was “Why not?” Paul Thomas Anderson had a small-scale, successful directorial debut with Hard Eight, bumped things up character and scale-wise with Boogie Nights, and then went for broke in a maximalist way with Magnolia. Anderson has expressed in more recent years that he believes Magnolia was too long, and his post-1999 work (like There Will Be Blood and The Master) has generally been more intimate and less sprawling, but when appropriately judged as a heightened, boldly moving, and melodramatic tearjerker, Magnolia is kind of perfect.

‘Magnolia’ Has Aged Surprisingly Well

Beyond just offering a certain kind of drama that’s rare to see in cinema, be it movies of old or modern-day releases, Magnolia’s relevance and importance today can also be seen through one of its storylines more than any other. As mentioned before, Tom Cruise is one member of Magnolia’s impressive ensemble cast, and has a role here that really goes against the likes of many of his other characters, including Ethan Hunt from the Mission: Impossible series or Maverick from the Top Gun movies. He demonstrates an immense amount of range here as a self-help guru/pick-up artist by the name of Frank T.J. Mackey, who espouses some horrifically misogynistic things to an audience of desperate young men, all of whom eat up every word he says, even if Mackey – based on the way he acts later in the film – might not believe such things with all his heart.

In an age where people have become famous online for saying similar things about women to young men, it’s this side of Magnolia that feels especially prescient. Sure, people practiced this kind of dangerous self-help before the internet was a thing, but it’s more noticeable than ever now, and it’s one part of Magnolia that feels more ahead of its time than anything else. If one can’t get on board with the melodrama, or the performances that almost feel like over-acting, or a couple of the aforementioned breaks in reality, then Magnolia should hold value for the Tom Cruise scenes. All in all, it’s a film about loneliness, isolation, and wanting to belong, with his character – and the character’s lessons – suggesting a heavily flawed way to go about changing one’s chances of finding things like sex, love, or even just human connection.

Why ‘Magnolia’ Still Feels Entirely Unique

Indeed, other great dramas released before and since 1999 have dealt with the same sorts of things Magnolia grappled with, and the filmography of Paul Thomas Anderson is packed with other classics – most of them dramas – that could be called more consistent. Though Magnolia does so much right, being packed with memorable shots, creative editing choices, great music (beyond just “Wise Up”), career-best performances from many involved, and a ton to chew on thematically, some might come away finding the whole thing over-stuffed. That could be by design. It’s hard, even after more than one viewing, to entirely get a handle on something so grand.

But therein lies the value of continually returning to something that was great in the 1990s, and might well be even greater now. Since Paul Thomas Anderson hasn’t tried to top Magnolia in terms of scale, and few other filmmakers seem willing to make something so long, melodramatic, and audacious, the things this film offers feel even more precious today. And the core technical qualities work just as well when viewed in the 2020s as they did in 1999, with certain things explored thematically – like Cruise’s character and his misogynistic sense of “self-help” – arguably becoming more relevant. You take what you can from an unusual epic like this, but rest assured: you will get something out of the 188 minutes you spend with Magnolia.